As you might have guessed (or observed), Tucker and I usually do our best to learn the languages of the countries we live in. Whether by way of formal university classes or informal lessons from native friends, Polish, Mandarin Chinese, Spanish, and French have all found their way into our homes, but recently, we found ourselves wondering which bits and pieces of these languages have stayed in our lives throughout the years and why. So, I did what I do best and made a list of our most-used non-English words (for possible future research, of course), and came up with:

Na zdrowie /nah zdrov.ee.yeh/

The first word, or in this case phrase, that fits the bill is definitely na zdrowie. It means “for health” in Polish and is used both when someone sneezes and as a “cheers” when clinking glasses. We typically use it in the sneezing scenario, and it never fails to elicit the fitting follow-up of “dzięki” (or even more frequently “dzięks”, the Poglish alternative). Why is this the call and response that stuck for something that obviously exists in English? No idea really, except that I think it’s way more fun to say!

Uwaga /oo.vah.gah/

The next word on the list has a clear reason for its common and continual usage. Uwaga means something like “attention” or “caution” in Polish, but it doesn’t sound so formal or pressing. It’s the one-word, light warning that we sometimes need, like for example, if there’s someone trying to get past the person you’re talking to or if there’s a puddle you’d rather your partner avoid. It’s too much to say “look out” or “caution”, but a little “uwaga” is perfect.

Laowai /lao.why/

Next up is laowai or “foreigner” in Chinese. This one we usually use out of politeness. When we need to specify someone not local to the area, “foreigner”, “outsider”, “gringo”, etc. all sound a little harsh to our ears, so instead we’ll throw out a “laowai”. It’s clear and to-the-point with a bit less emotional baggage/pejorative connotations. Sometimes I really miss the bluntness of Chinese, but then I remember having to shout “fuwuyuan” or “waiter” at restaurants, and on second thought, I’m all good.

Cha bu duo /cha boo do.wuh/

Another phrase that we still find ourselves using post-China is cha bu duo, which literally translates as “not much difference”, but is used more or less like “good enough”. It’s something we use when events don’t exactly go to plan, but the end result is perhaps the best we (or anyone) could manage in the given situation. It’s a verbal shrug if you will, and somehow we find ourselves using it a lot.

Sip /seep/

Now onto probably the most used word on this list, one that I would conservatively guess we use daily: sip. It’s something we picked up in Mexico and haven’t dropped despite confused looks on various Quebecois faces. “Sip” is the Spanish equivalent of “yep”, and it’s just so quick and easy that it slips out all the time, even when we’re clearly not speaking Spanish with anyone.

Ojalá /oh.ha.la/

Another commonly used Mexican Spanish word in our house is ojalá. Ojalá might just be my favorite Spanish word punto because it has such a great etymology and is incredibly useful. It means “hopefully” but can also be used at the end of a thought to mean something like “fingers crossed” or “inshallah” (”if God wills it”), which is where it originally came from. For example, will we continue to grow our collection of amazing international words and phrases? ¡Ojalá!

Oh mon Dieu /oh mon dee.oo/

Speaking of Allah or Dieu, another non-English phrase we tend to favor over any English alternatives is oh mon Dieu. Maybe it’s because “oh my God” sounds a bit strong in English, while “omg” makes me sound like I’m twelve. Or maybe it’s just the perfect amount of French drama, but nothing feels more theatrical than an eyeroll and an “oh mon Dieu”.

Dangereux /dan.zher.oo/

And last but not least is another one we tend to sub out just because it’s way more fun to say: dangereux. It’s French for “dangerous”, but again I think it just gives the situation a certain je ne sais quoi, non ? The next time you want to playfully point out some implicit danger, I recommend using “dangereux” with just the right amount of emphasis – quel drame !

Okay, they might not be on par with “schadenfreude” or “fetch”, but these are definitely some fun and useful words as far and Tucker and I are concerned, and I sincerely hope you’ll start using them in your regular speech! Ojalá the next time we chat, you can be inducted into our weird little linguistic mélange. Until next time! Na zdrowie!

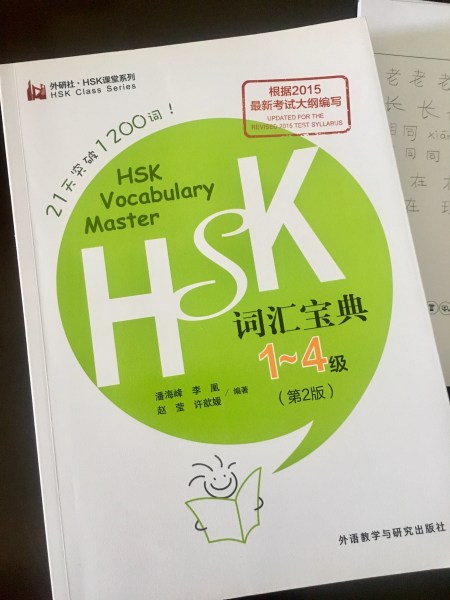

One of my goals this year, as I mentioned in my last post, is to really focus on my Mandarin skills. I’m planning to take the HSK before we leave next summer, and I’d really like to do well. The HSK is a Chinese proficiency test for foreigners learning the language. The highest score is a 6, which would demonstrate “a learner who can easily understand any information in Chinese and is capable of smoothly expressing themselves in written or oral form”. I’m aiming for a 3 (haha!), and since I’m likely going on this journey alone (Tucker really has no interest), I’d like to at least share a little bit about what makes Chinese such a difficult language to learn.

One of my goals this year, as I mentioned in my last post, is to really focus on my Mandarin skills. I’m planning to take the HSK before we leave next summer, and I’d really like to do well. The HSK is a Chinese proficiency test for foreigners learning the language. The highest score is a 6, which would demonstrate “a learner who can easily understand any information in Chinese and is capable of smoothly expressing themselves in written or oral form”. I’m aiming for a 3 (haha!), and since I’m likely going on this journey alone (Tucker really has no interest), I’d like to at least share a little bit about what makes Chinese such a difficult language to learn.

Another problem we often encounter with pinyin is that it is more often than not missing the diacritic marks. Those marks represent the four tones of Mandarin, and are essential in its pronunciation. Unlike in English, changing the pitch of your voice while speaking Chinese can actually change the words you are saying. The pronunciation of mā (“mom”), má (“hemp”), mǎ (“horse”), and mà (“to scold”) only differs in tone. Unfortunately for lazy, toneless English speakers (like me), this makes it really hard for native Mandarin speakers to understand exactly what we’re saying. We try for “mom” and end up with “horse”, something which I hope has been more entertaining than irritating for them!

Another problem we often encounter with pinyin is that it is more often than not missing the diacritic marks. Those marks represent the four tones of Mandarin, and are essential in its pronunciation. Unlike in English, changing the pitch of your voice while speaking Chinese can actually change the words you are saying. The pronunciation of mā (“mom”), má (“hemp”), mǎ (“horse”), and mà (“to scold”) only differs in tone. Unfortunately for lazy, toneless English speakers (like me), this makes it really hard for native Mandarin speakers to understand exactly what we’re saying. We try for “mom” and end up with “horse”, something which I hope has been more entertaining than irritating for them! Train = Fire + Car

Train = Fire + Car Alright now! Who’s ready to learn this with me?! Chinese is definitely a language on the rise as far as power and prestige go. Much like what happened to English in the 1700s, increases in immigration, tourism, and business are spreading Chinese to all parts of the globe. In Australia, I was surprised and delighted to find Mandarin on most signage, and, even in Georgia/Florida (quite far away from China), maps and other tourist information can often be found in Mandarin. Some linguists refer to Chinese as the language of the future, and while right now it’s more painfully in my present, I hope to keep it around for my future as well! Wish me luck!

Alright now! Who’s ready to learn this with me?! Chinese is definitely a language on the rise as far as power and prestige go. Much like what happened to English in the 1700s, increases in immigration, tourism, and business are spreading Chinese to all parts of the globe. In Australia, I was surprised and delighted to find Mandarin on most signage, and, even in Georgia/Florida (quite far away from China), maps and other tourist information can often be found in Mandarin. Some linguists refer to Chinese as the language of the future, and while right now it’s more painfully in my present, I hope to keep it around for my future as well! Wish me luck!